In mid-’90s buyers could find themselves having surprisingly many options when it comes to buying a Pentium-class CPU.

The original Socket 4 60 and 66 MHz Pentiums were replaced by more efficient 90 and 100 MHz models for Socket 5, but some old stock was still available for some time. Shortly after that Intel introduced a new value-oriented Pentium 75 MHz chip.

At around the similar time, the i486 line-up was reinforced by clock-tripled DX4 chip which, thanks to high frequency and improved L1 cache, prolonged life of the Socket 3 platform. And finally in 1995 Intel introduced long-promised Pentium Overdrive chip that allowed 486 owners to upgrade their systems to genuine Pentium architecture.

Other vendors were catching up. Surprisingly, it was neither of the traditional Intel competitors to challenge Intel on 5th gen. design. The first alternative came from NexGen. Nx586 was a clean-room CPU design based on RISC technology. Both AMD and Cyrix struggled with producing 5th generation chips and their efforts had long delays, but they eventually succeeded and in 1996 and brought their AMD K5 and Cyrix M1 (6×86) chips on the market. In the period before that, they attempted to compete with M1sc design (5×86 chip) or AMD X5 (Am 5×86) on the Socket 3 platform.

The above-mentioned CPUs loosely define the group of CPUs that is the subject of our test today. We are trying to find out which early Pentium chips were the best and how they compare to each other. Since many of these chips carried “P75” rating we are looking for a Pentium 75 killer.

Rules of engagement

In this competition, we’ll be comparing CPUs on their most typical period-correct platform. That means:

- Pentium 60 and 66 MHz on i430LX based motherboard with 256k of asynchronous cache and 16MB FPM RAM

- Pentium 90 and 100 MHz on i430NX motherboard with 256kB of asynchronous and 16MB FPM RAM and for reference results will be captured on i430FX motherboard with 256kB of pipelined-burst cache

- Pentium 75 and AMD K5 PR75 will be run on i430FX motherboard with 256kB of pipelined-burst cache and 16MB EDO RAM

- Nx586 chips will run on Alaris reference board with NxVL chipset, 256kB of asynchronous cache and 16 MB FM RAM

- Socket 3 chips (Am5x86, Cx5x86, DX4-100 and Pentium Overdrive 83) will run on MSI-4144 motherboard with SiS 496, 256kB asynchronous cache and 16 MB of FPM RAM

In all cases, the VGA card is Diamond Stealth 64 with Trio64 chip and 2MB DRAM. Storage is SD-SCSI v6 device connected through Adaptec controller.

We’ll be comparing in different workloads in both DOS and Windows 3.11.

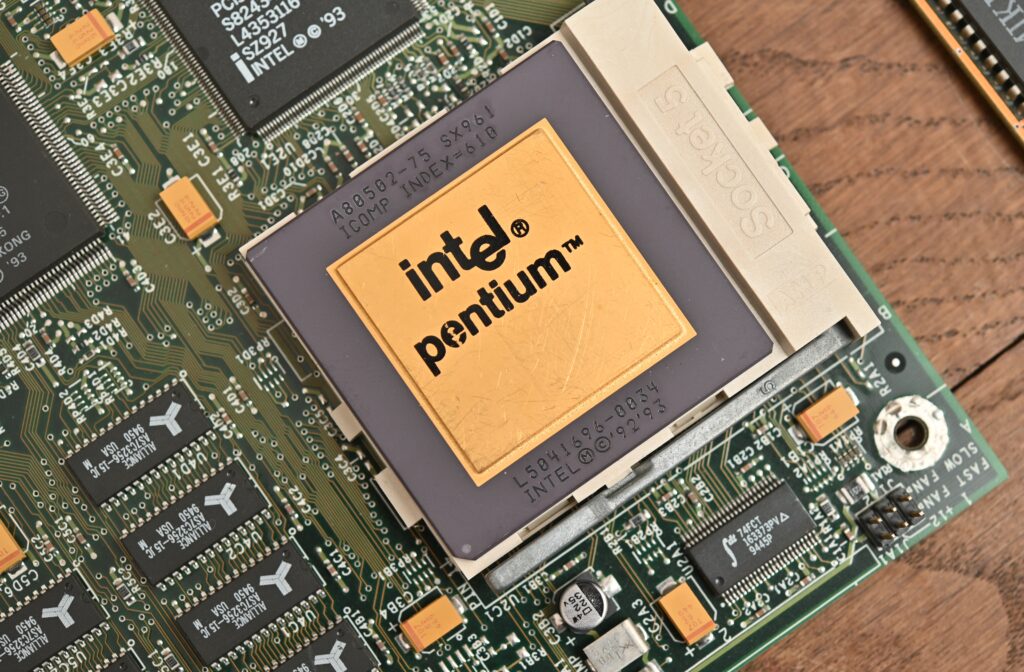

Pentium 60/66 MHz

Those were the original 5V 0.8μm Pentium designs. The Pentium was a revolutionary chip in March 1993. Clock by clock much faster than the original DX2-66 it replaced. The natural habitat of P60/66 was Intel i430LX Mercury chipset with short-lived Socket 4 which somewhat limited their potential. As much revolutionary as in March 1993, it was clear from day one that those stop-gap products until the 0.6μm process is mastered enough for CPUs to move to 3.3V world.

Once the breathtaking performance of P60/P66 is only average when compared to more modern chips. One problem is that some while competitors can benefit from the modern motherboard, the P60/66 remains in 1993 as far as memory or cache interface is concerned. There simply isn’t a better chipset than i430LX.

Pentium 90/100 MHz

Introduced year after the first Pentium it was what the original P60/P66 line-up should have been. Those were very powerful chips in 1994. They came on a new i430NX (Neptune) platform which allowed for multiple-CPU configurations and an insane amount of RAM. Eventually, they got even better when the i430FX Triton chipset was introduced a year later. However, in this test, we’ll be running them just like their first customers – on Intel Neptune based board.

The P90/P100 ruled the world in 1994 and still rocked it in this test. Surprisingly this is both with the old 1994 chipset and especially with the 1995. Some other chips might overtook it in some syntactic benchmarks, but the overall crown still gets to P100 followed by P90. It is not without surprise that the P90 with 430FX chipset easily beats the P100 on the old chipset.

Pentium 75

Introduced in October 1994, it was the first affordable Pentium for many. That’s what the author of this article used one back in the days. Having 50 MHz and only 25 MHz PCI bus the performance was a clear step back compared to the original 66 MHz chip. However, it was clocked a bit higher and more importantly, it was usually running on a more efficient chipset, which helped to win back its handicap in many workloads.

Clearly, the relatively slow 50MHz front-side bus combined with having only 25 MHz PCI bus noticeably reduces of the P75. In pure synthetic loads, the P75 can hold its own, but in “standard” benchmarks the P75 got beaten by some of the other chips, including the older P66. The P75 can greatly benefits from the Triton chipset.

Intel DX4 100 MHz

Introduced alongside with the P90, it was a very smart choice for many users. As much as Pentium was revolutionary in 1993, not many applications were initially optimised for the new architecture. Until developers got it how to write code optimised for dual-pipelines and fast FPU, many users found that a higher-clocked 486 is more than adequate if not slightly faster for contemporary software. At the end of its life, the DX4 got a small tweak in the form of write-back mode for its L1 cache which is the one that was used in this test.

Given by the specs, the triple-clocked 486 as the least advanced design, was expected to finish last in this competition. However, the fast motherboard helped to get in front of NexGen and even P60 in some tests. The write-back enabled (&EW) variant of the chip provided just a bit of extra juice over the standard write-through (&E) variant.

NexGen Nx586 P80/P90

The first 5th generation Pentium competitor was a clean-room design by a small designer company – NexGen and manufactured by IBM. Rather than piggybacking upon 486 or Pentium socket, it came on its own motherboard (originally VL-Bus and later PCI) with dedicated socket and first-party NexGen chipset. Motherboards featured truly unique features such as a dedicated bus which was not common until Pentium Pro or 4-way set associative L2 cache. Inside it was even more forward-thinking. The RISC core with x86 decoding front-end was a really an advanced design for its days. One could say that it was perhaps too ambitious as so much silicon budget was spent on advanced core and not enough left for the FPU. The Nx586 CPU got only limited success, but become a proving ground for the very popular AMD K6 processor when the NexGen company was acquired by AMD in 1995.

Despite promising specs, the performance of Nx586 proved to be rather disappointing. It most tests, both NexGen CPUs lost even to the DX4. It was also a very difficult chip to test. The absence of FPU rendered it unable to run many tests altogether.

Pentium Overdrive 83 MHz

Provided an upgrade path for 486 systems to P5 architecture. Until 1996 everybody had Overdrive sockets in their 486’s but the chip was nowhere to be found. When it finally arrived, the market was full of other options. Technologically it was still an interesting chip – a true P54C Pentium with all its benefits sitting on 32bit 486 bus. The wider bus was compensated by doubling the L1 cache which was a fair trade-off. Being a 3.3V chip it also featured integrated 5V -> 3.3V converter enabling it to be installed into old Socket 2 motherboards. However, as those were created against the spec many years before the actual chip was available the compatibility issues were common.

The performance of PODP83 is excellent. The Pentium architecture and fast 1995 motherboard catapulted the chip right in between the P75 and P90. Clearly the best choice for Socket 3 platform.

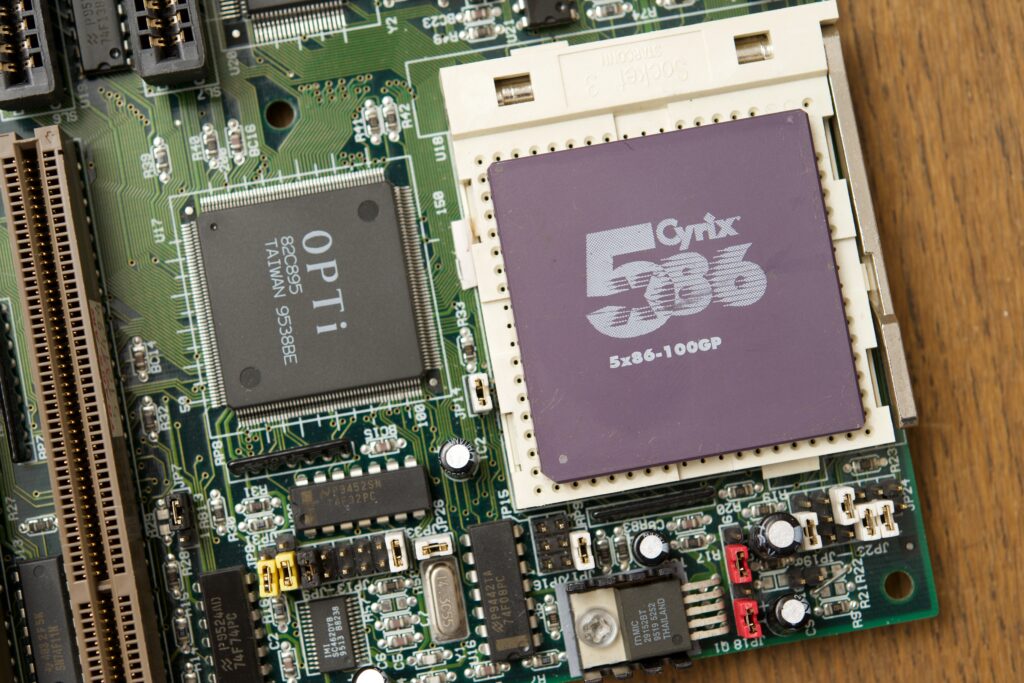

Cyrix 5×86-100GP

This Cyrix designed and IBM manufactured chip was a progressive design for the 486 platform. Featuring generous cache architecture and advanced features that rival or exceed even the true Pentium chip. However, several of those did not work as planned and had to be disabled in production chips to maintain compatibility and stability. In this test, we’ll be running the CPU in default configuration without any extra tweaks.

The 5×86 had many promises, but the performance in the test wasn’t spectacular. It barely managed to beat the DX4-100 and the Am5x86 or Pentium Overdrive was too much. Please note that the CPU was tested in stock config. Had any of the disabled features been enabled, it would perhaps perform a little better.

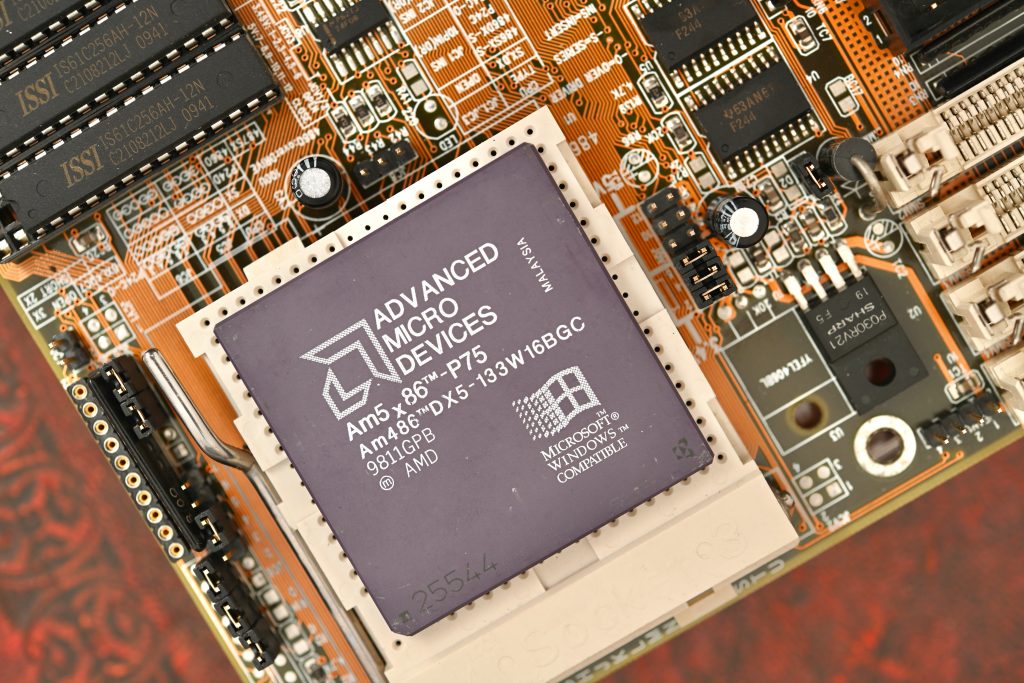

AMD X5 5×86-133 P75

AMD took a different approach with their 486 upgrade chip. Rather than using 5th generation features they simply scaled their 486 design. The high clock proved to be working very well for the contemporary software and the CPU was competing favourably with bottom-end Pentiums let alone older 486 parts.

The 5×86 is a performance king of the Socket 3 platform. The very fast clock speed can even help it to beat some of Pentium chips. Especially in simpler game tests like DOOM where the advanced architecture doesn’t help that much.

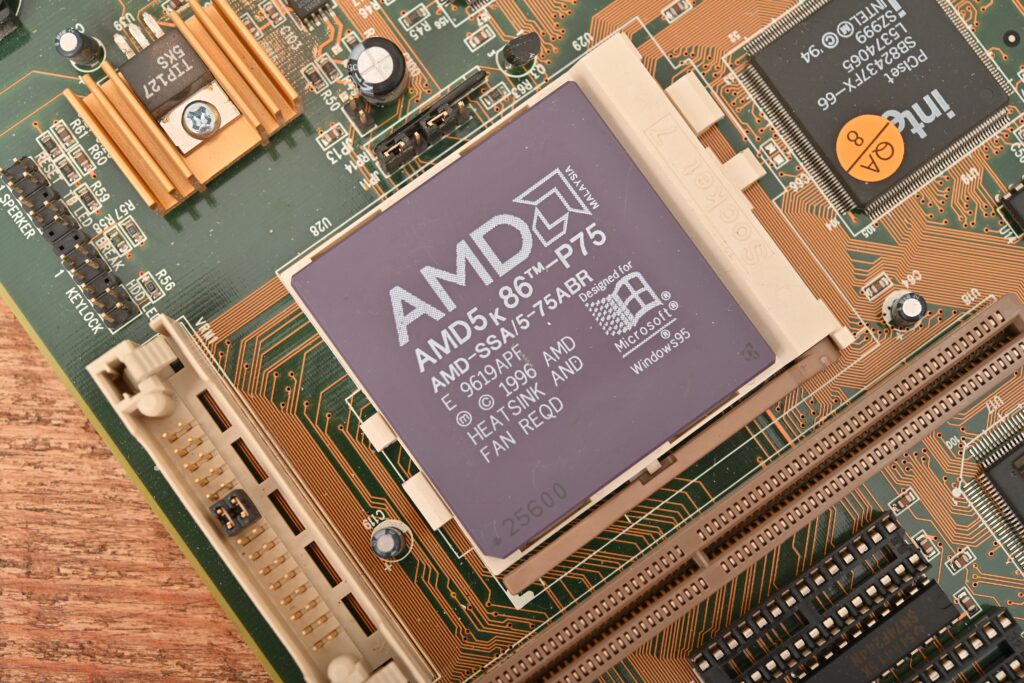

AMD 5k86 P75 (K5)

It took a while for AMD to bring its true 5th generation chip on the market. In many ways, it was similar to the Nx586. It also featured a RISC core with x86 frontend and advanced multi-scalar architecture. Despite a very solid decent performance the design proved to not scalable enough so AMD decided to move on and used the Nx686 design for their K6 successor.

The 5k86-P75 is technologically the most advanced CPU inthe competition. It mastered synthetic integer ALU tests, beating even the P100. The K5 also enjoyed the benefit of being run on the Triton chipset in the test. On the other hand, the non-pipelined FPU part is the weak part of the architecture. Twice slower than Intel P75 but still a bit ahead of 486-class chips. Despite the above the K5 failed to materialise its architecture in application tests (Quake, Winstone95), the K5 finished just behind the P75. It looks like its power can be only unleashed when running the right kind of software.

The results

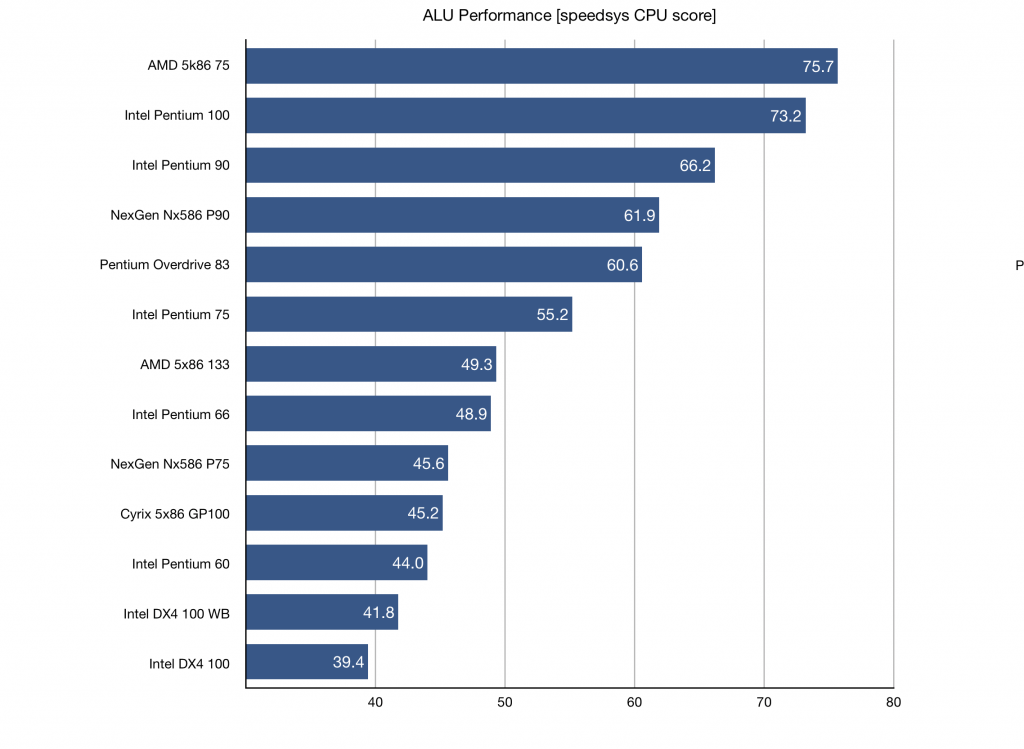

Pure ALU performance

The CPU score is a pure synthetic test measuring the theoretical performance of the integer part of the chips. The tests fit almost perfectly to even the smallest L1. Neither chipset/cache performance nor RAM speed doesn’t help here. All that matters is the internal architecture and the CPU clock. This AMD 5k86 excelled in this test followed by Pentium chips. It is also the only chip where Nx586 parts confirmed its P ratings. However, this is just a warming round.

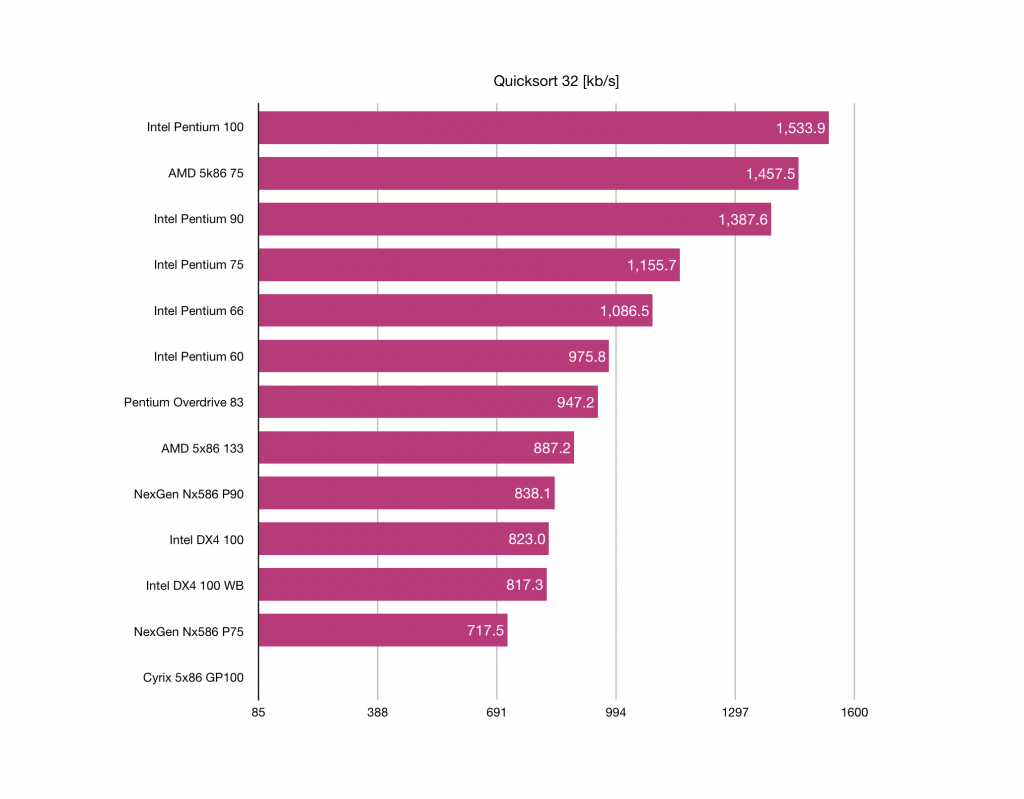

Quiksort32

Quake framerate

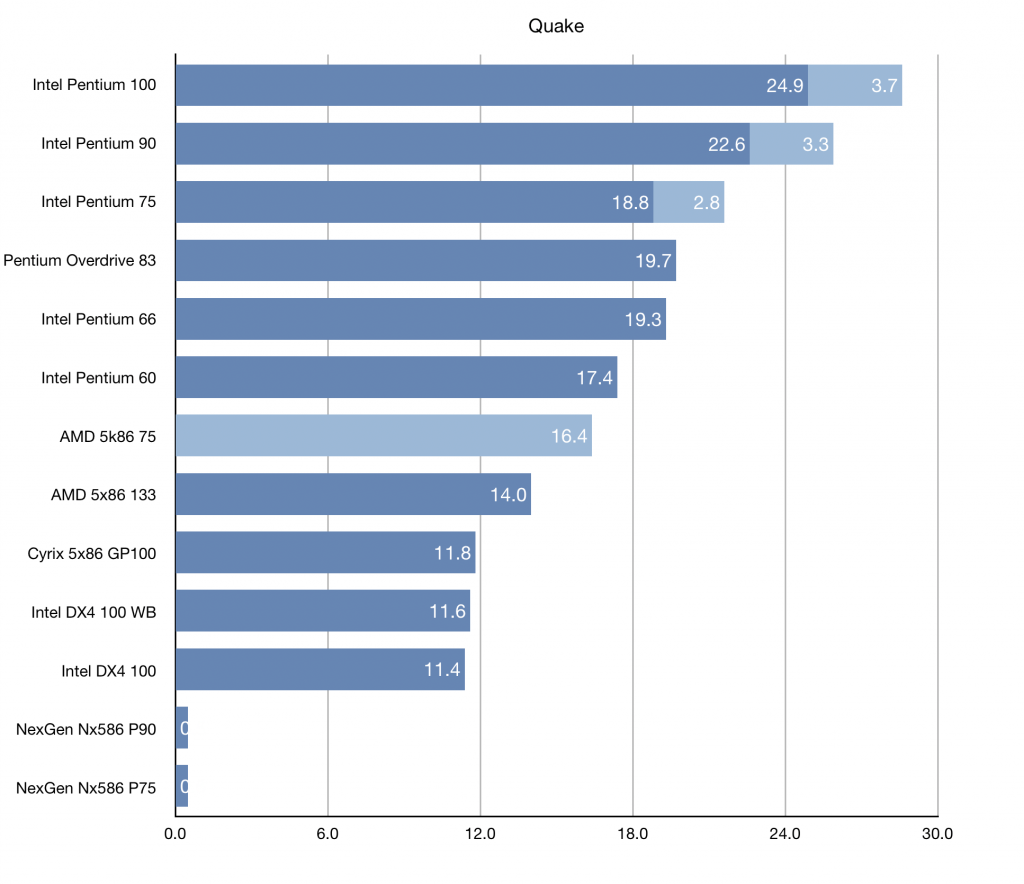

Quake is my favourite benchmark. It captures CPU/FPU performance as well as the speed of L2 cache and RAM.

Obviously having no FPU, the Nx586 is in serious problems here. The results obtained are with using SW FPU emulator which is not really viable. Other CPUs fare much better, but it is clear that Pentium’s FPU is out of reach of any competition. Even a higher clocked 5k86 would have a serious problem here. The results also show that the Intel Trion (results in a lighter colour) chipset gives all CPU a nice boost, but doesn’t fundamentally change the landscape.

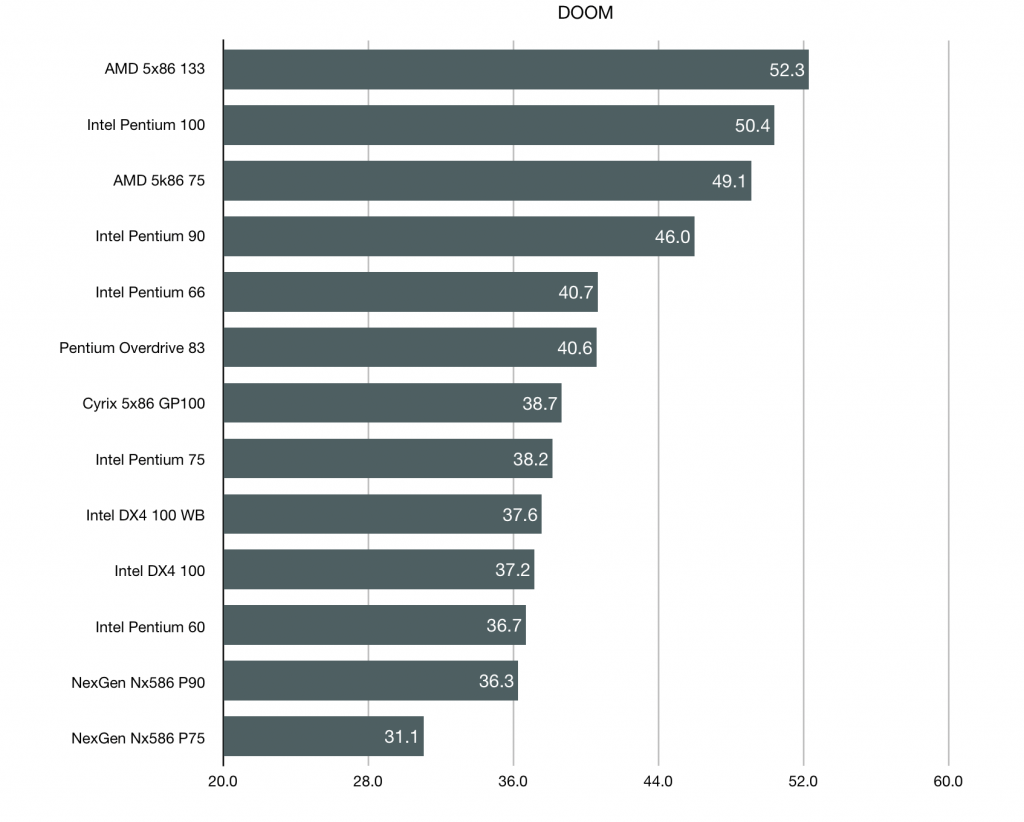

DOOM

DOOM is a wonderful game, but a very poor hardware benchmark. The relatively simple game engine combined with inefficient frame-buffer handling created a discipline where there is a surprising winner – AMD 5×86. Hard to explain why, but whatever it is, clearly the internal frequency plays a big role in that.

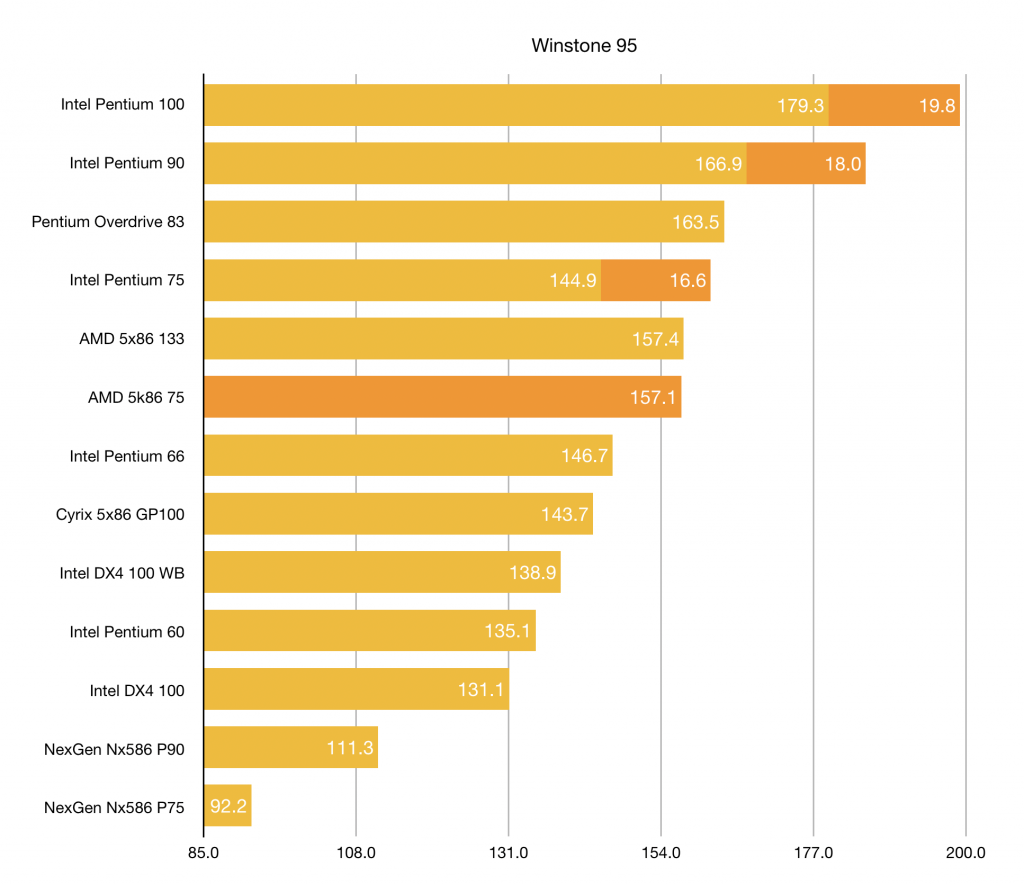

Winstone 95

This might be the most representative test. A blend of scores captured when running a popular business productivity software like Word, AmiPro, CorelDRAW! and more.

Pentium chips lead the pack again with or without the help of Triton chipset. The Pentium Overdrive 83 performs also very well getting well in front of the P75 in this test. Surprisingly, the chip I expect to perform strong- the 5k86 returned only average performance and has been beaten slightly by the older 486-based 5×86 chip. NexGen chips suffered again losing even to 486 parts.

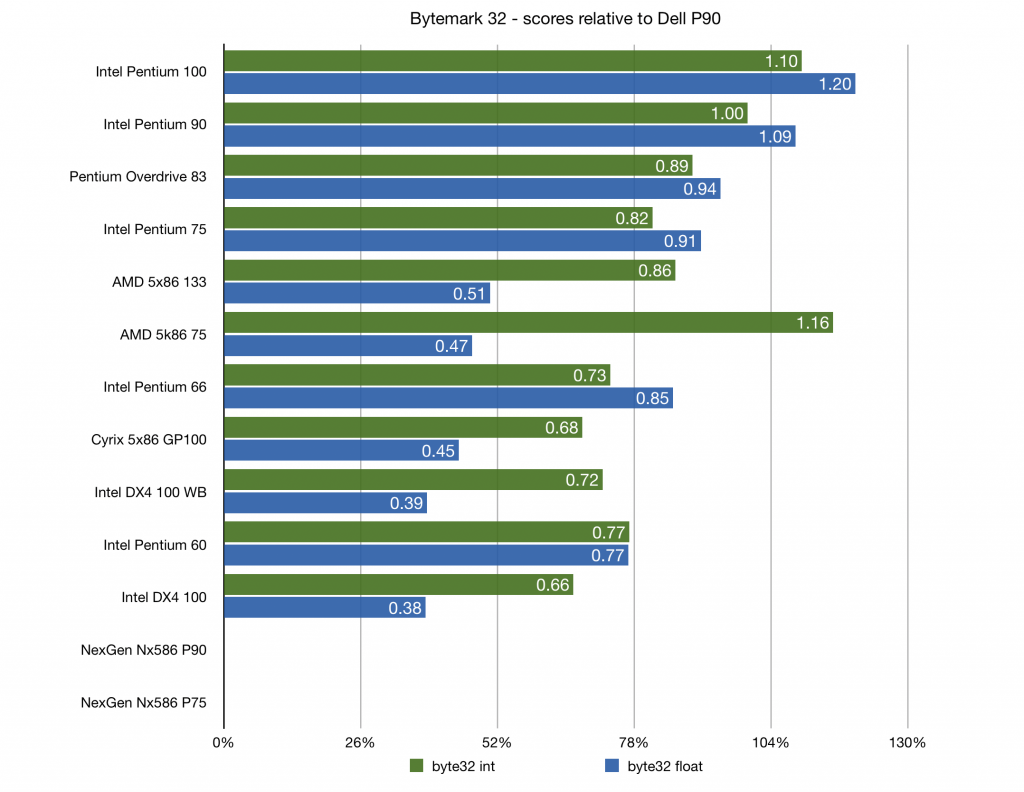

Bytemark32

Bytemark32 (later called nbench) is a popular synthetic test exercising both CPU and FPU. It executes various algorithms. What matter most in this test is the architecture of the CPU and its internal cache. Everything else is secondary.

This test confirms the strong showing of 5k86 in integer ALU performance and mediocre FPU performance.

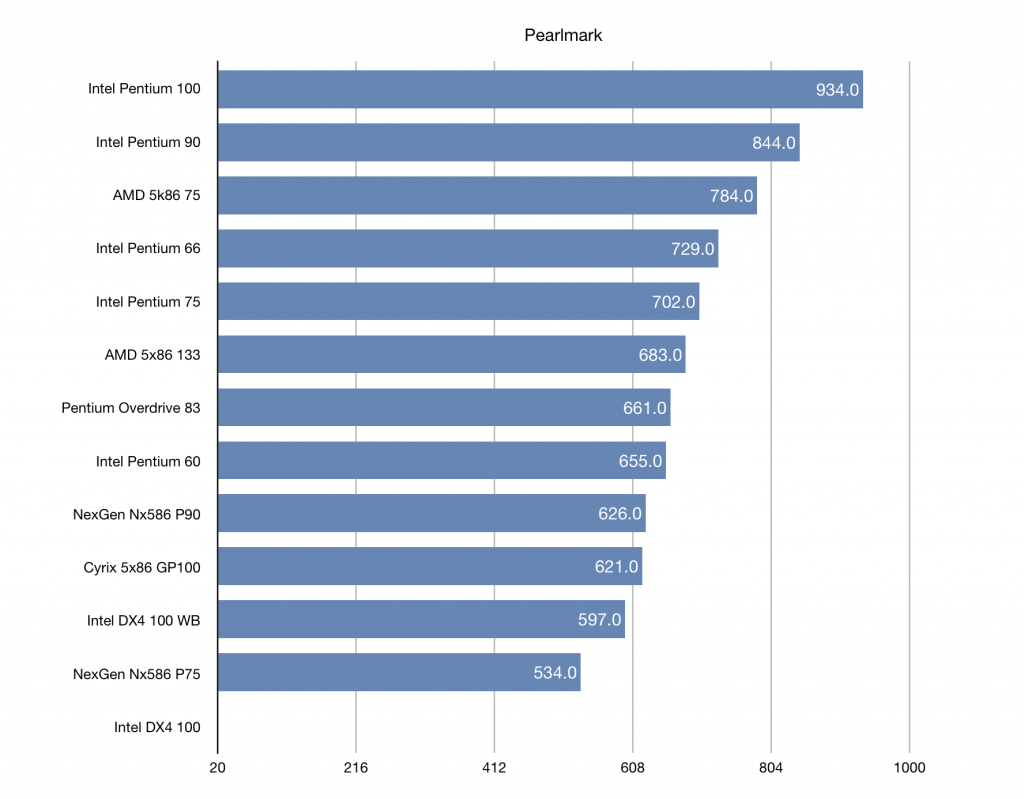

Pearlmark

Pearlmark is a simple integer benchmark from 1995 displaying a software-rendered animated logo. The results are not surprising with Pentium 100 winning and the rest of the field sorted in a familiar order.

Great review and comparison!

It would have been fun to see both Intel and AMD staying longer with the old cores and pushing them to 166, 200 or even 233.

Take care,

Viktor

I agree a super clocked 8086/80286 or 80386/80486, would have been interesting, but the difference between the various 586/Pentium cores was a complete mess.

Totally! Could have continued pushing faster too as better fabbing became available. Would have been interesting to see what that evolution would have looked like.

I’d like to see the nx586 PF110 and see how it measures up on this. It runs at 102Mhz I believe.

the 586 133 is a jumper away from 160 mhz pure performance 😀

Yep! And 6x might have been the tip of the iceberg if development would have continued. Imagine a 10x or 20x multiplier. 😀

Wow great comparison here too!

Thanks a lot!

I’d have loved to see how the AMD 486 DX4 120 would have scored in there…

Absolutely! That was one of the fastest chips available back then since it was using 40Mhz vs 33Mhz. What would have been even more interesting is if it would have been pushed further–5x or 6x or more. I think if it would have been possible and cheap enough, desktops wouldn’t have seen as they would have only been for servers, similar to the xeon series today.

This is a great website with lots of information, and i greatly thankyou for your time! My only minor criticism is the use of truncated bar charts. Its very difficult to grasp the actual differences with dyslexia when these are used.

thanks hugely!

It’s very interesting to notice how the Triton chipset helps the Pentium 75 in a couple of important tests so much to change its ranking. Probably, the Triton’s design (better cache?) is capable of compensating the poor bus speed of the P75, which runs at merely 25 MHz.

Am I correct?

Thanks